The Revolutions

When Governor-General Jose de Basco y Vargas arrived in the Philippines, the Galleon Trade had not yet begun. However, the islands already had existing trade relations with countries such as China, Japan, Siam (now Thailand), India, Cambodia, Borneo, and the Moluccas (Spice Islands). These trade relationships were maintained by the Spanish government, with Manila emerging as the central hub of commerce in the East. At the time, the Philippines, ostensibly a Spanish colony, was governed rom Mexico. In 1565, the Spaniards restricted access to Manila's ports, allowing only Mexico to engage in trade. This gave rise to the Manila-Acapulco Trade, which is more commonly referred to as the "Galleon Trade."

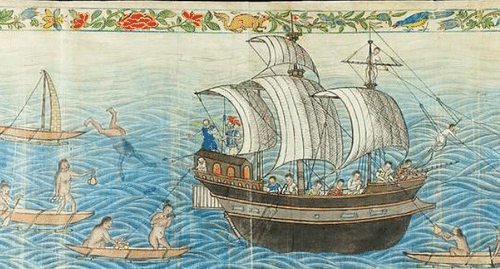

Galleon Trade

The Galleon Trade was a government monopoly. It was a ship (“galleon”) trade going back and forth between Manila and Acapulco in Mexico. Only two galleons were used: one sailed from Acapulco to Manila with some 500,000 pesos worth of goods, spending 120 days at sea and the other sailed from Manila to Acapulco with some 250,000 pesos worth of goods spending 90 days at sea. It started when Andres de Urdaneta, in convoy under Miguel Lopez de Legaspi, discovered a return route from Cebu (from which the galleon actually landed first) to Mexico in 1565. This trading system served as the economic lifeline for the Spaniards in Manila, serving most trades between China and Europe. During the heyday of the galleon trade, Chinese silk was by far the most important cargo. Other goods include tamarind, rice, carabao, Chinese tea and textiles, fireworks and tuba were shipped via the galleon including exotic goods such as perfumes, porcelain, cotton fabric (from India), and precious stones. After unloading at Acapulco, this cargo normally yielded a profit of 100-300% and on its return voyage, the vessel brought back huge quantities of Mexican silver and other prized flora and fauna such as guava, avocado, papaya, pineapple, horses, and cattle. Governor Basco thought of making an organization, the Royal Philippine Company, that will finance both the agricultural and the new trade that were being made between the Philippines and Spain, and other Asian countries. Some groups like the Catholic Church opposed the new organization as changes brought by the planned reforms and traders of the Galleon trade were not accepted. There were news that the Royal Philippine Company had issues of mismanagement and corruption. But the governor-general still continued to develop reforms that he prohibited the Chinese merchants from trading internally. He also introduced the development of cash crop farms (crops cultivated for export) and became very strict to some policies that allow the continuous opening of Manila to foreign markets; And finally, he also established monopoly and maximize the production of tobacco.

The tobacco industry was under the government control during General Basco’s time. In 1871, the first tobacco monopoly was established

in Cagayan Valley, Ilocos Region, La Union, Isabela, Abra, Nueva Ecija and Marinduque. These provinces were the only ones allowed to

plant the tobacco, and this is the only plan that was allowed to be planted on the farmlands.

The government exported tobacco to other countries and part of it were given to the cigarette factories in Manila.

The first among the revolutions was the Industrial Revolution, which was about the inventions of steam engines and machines that were used in the manufacturing sector in different cities of Europe. This revolution was considered as one of the most significant developments in the 19th century — from being a country that relied on machines and wage labor, Europe’s economic status totally changed. At this time, traders were fortunate to become the first capitalists. The industrial workers were former farmers who migrated from rural areas and remote provinces of Europe.

From this, positive effects took place as the industrial revolution contributed many things to the people:

1. The Philippines was opened for world commerce.

2. Foreigners were engaged in manufacturing and agriculture.

3. The Philippine economy became dynamic and balanced.

4. There was rise of new influential and wealthy Filipino middle class.

5. People were encouraged to participate in the trade.

6. Migration and increase in population were encouraged.

The Galleon Trade ended in 1810 as a consequence of the Mexican War of Independence leading to the loss of Latin American colonies from the Spanish empire. Consequently, the Royal Philippine Company was shut down and trade policies were adjusted, leading to Manila being opened for global trade in 1834. Merchants and traders from various countries settled in Manila, establishing merchant houses and leading financial sectors, enabling the export of agricultural cash crops. These merchants were mostly mestizos, of Spanish and Chinese descent. Ilustrados, members of the landed upper class, could afford to send their children to Spain and Europe for advanced education, thereby gaining social equality with the Spaniards. The struggle for equality and secularization were significant issues during this period. The period also saw infrastructure improvements such as the construction of railways, steamships, and bridges for better transportation and communication. The opening of the Suez Canal on November 17, 1860, provided a shorter trade route and enhanced the Philippines' global interactions. The Philippine economy began to prosper through cash crop exports. Most of the country's export revenue in the nineteenth century came from cash crops such as tobacco, sugar, cotton, indigo, abaca, and coffee, underlining the importance of land ownership at that time.

1st Peninsulares (pure-blooded Spaniard born in the Iberian Peninsula such as Spain)

2nd Insulares (pure-blooded Spaniard born in the Philippines)

3rd Spanish Mestizo (one parent is Spanish, the other is a native or Chinese Mestizo; or one parent is Chinese, the other is a native)

4th Principalia (wealthy pure-blooded native supposedly descended from the kadatoan class)

5th Indio (pure-bloodedd native of the Philippines or the Filipinos)

6th Chino Infiel (non-Catholic pure blooded Chinese)

BOURBON REFORMS AND CADIZ CONSTITUTION

The Spanish monarchs decided on implementing Bourbon reforms, a set of economic and political laws that

contributed to the expansion of the gaps between the peninsulares and the creoles (those born in America). This made the independence of the Spanish American colonies possible through a revolution. The Bourbons’ purpose was to strengthen and support the Spanish empire during the 18th century but led to its destruction in the nineteenth.

During the reorganization of the colonial military, the bourbons sought to ensure that all officers

were Spanish born, but it was difficult for them to apply the policy because most of the officers were natives,

although the highest ranking officials belonged to the Peninsulares. Said reforms were aimed at the following:

1) to control over the American colonies;

2) for the crown to obtain resources through exploitation;

3) to professionalize the army;

4) to subdivide New Spain into mayors;

5) to diminish the viceroy’s political power; and

6) to prohibit the natives from participating in political or ecclesiastical commands.

These reforms emerged because of the need for free trade and open new ports to improve trading with other countries; to promote

the extraction and processing of silver by putting up a college of mining and the court of mines, and to evict the Jesuits from the Spanish

territories since they were disobedient before Spanish empire. The reforms achieved in growing the production, trade and income was not that easy.

Meanwhile, around 300 subordinates from Spain, Spanish America, and the Philippines decided to form a liberal constitution in the Mediterranean port of Cádiz in 1812, in the middle of the occupation of almost all of the Iberian peninsula by the French army. The constitutional monarchy that the Constitution of 1812 tried to put in place did not materialize because King Fernando VII declared it invalid and restored absolutism in May of 1814. However, Cádiz and the Constitution of 1812 were among the very important periods in the political and intellectual history of the Spanish-speaking world and represent a major contribution to the Western political thought and practice during the Age of Revolutions.

The study of the Cádiz Constitution, of liberalism, and of its manifold relations with Spanish America during the first quarter of the 19th century has shown such a revival in the past two decades that it may be a temptation to say that this is a “new” field in the Western academic world. The problem is, any English-speaking scholar who cannot read Spanish will not be able to do so because most of the bibliography is in Spanish. Studies of the Cádiz Constitution and liberalism up to the recent years were almost exclusively confined to the Peninsula where Spanish America is now a very large field of research regarding these topics.

The bicentennials of

1) the beginning of the crisis of the Spanish monarchy or crisis hispánica (2008),

2) of the beginning of the “independence” movements in Spanish America (2010), and

3) of the promulgation of the Cádiz Constitution (2012) have been the main motives behind the editorial avalanche on these topics that were witnessed for the past years.

In any case, the importance of the participation of the Spanish American deputies in the Cádiz Cortes and of the role that the Spanish liberals thought in general, not to mention the Cádiz Constitution in particular that was played in Spanish America during the first quarter of the 19th century are now well-established.

The 1812 Constitution was deemed essential if one is to understand the political, ideological, and intellectual aspects of liberalism. With all its limitations and its very restricted application in the Peninsula, it was revolutionary vis-à-vis the political principles that had sustained the Spanish monarchy for centuries.

Cádiz was, more than anything else, a political revolution; however, this fact should not neglect or minimize the social and cultural implications of a period of the history of the Spanish-speaking world that evidently transcends a legal document. Because Cádiz, liberalism, and the 1812 Constitution are the main objectives of this bibliography, it centers its attention in Peninsular Spain during the six years that cover the crisis hispánica and the revolución liberal española (i.e., 1808–1814) and in Spanish America during those six years and the following decade, all through which the presence, weight, and influence of what was still the metropolis was felt in the entire region (with considerable variations among the different territories).

Liberals then returned to power in Spain and the Cádiz Constitution was brought back in 1820. The Trienio Libera period lasted only three years and could not avoid the loss of the whole continental Spanish American empire.